We knew that coming up here food variety would be limited, so we decided to bring the widest selection of non-perishables we could. That mostly turned out to be all sorts of dried spices. Since they arrived our diets have been far more exciting, but there’s so many of them that they hardly fit in the kitchen closets.

Time to build a spice rack!

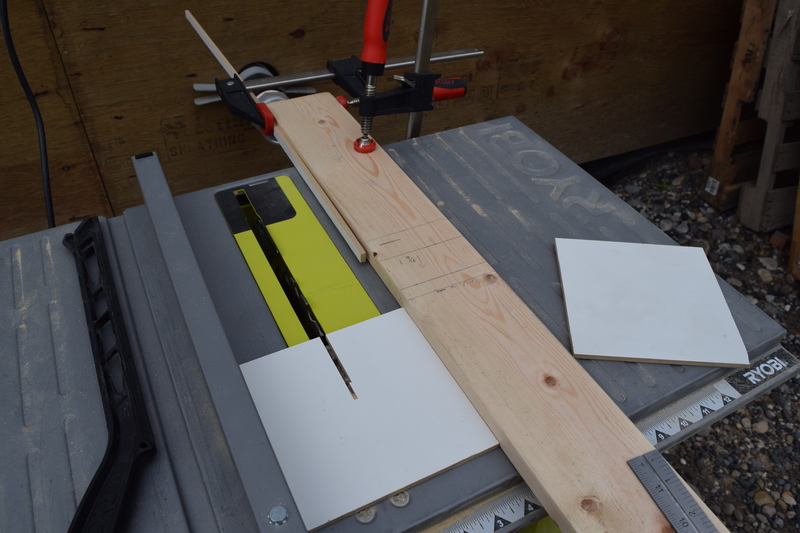

I had the idea when I found an still-almost-new Ikea dresser that someone had tossed out at the dump (the dump here is fascinating, I’ll do a whole blog post on it soon). I grabbed two thin slide-outable sheet of white Ikea particle board out of the back of it.

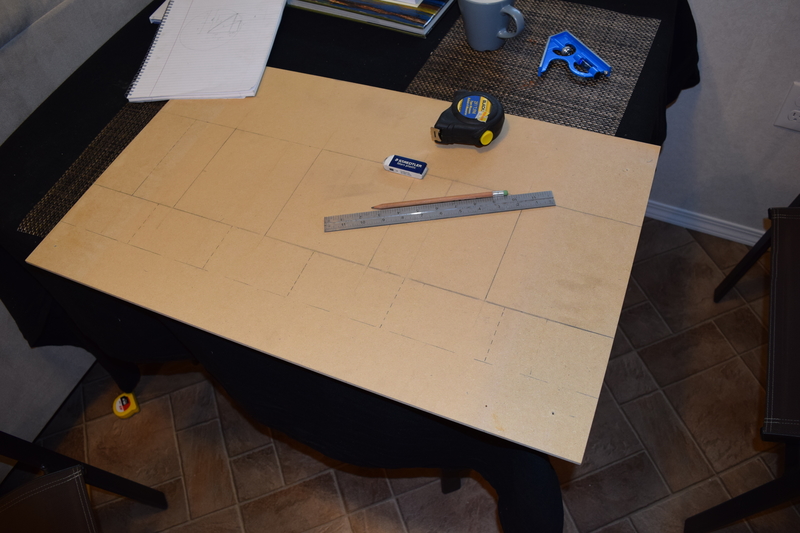

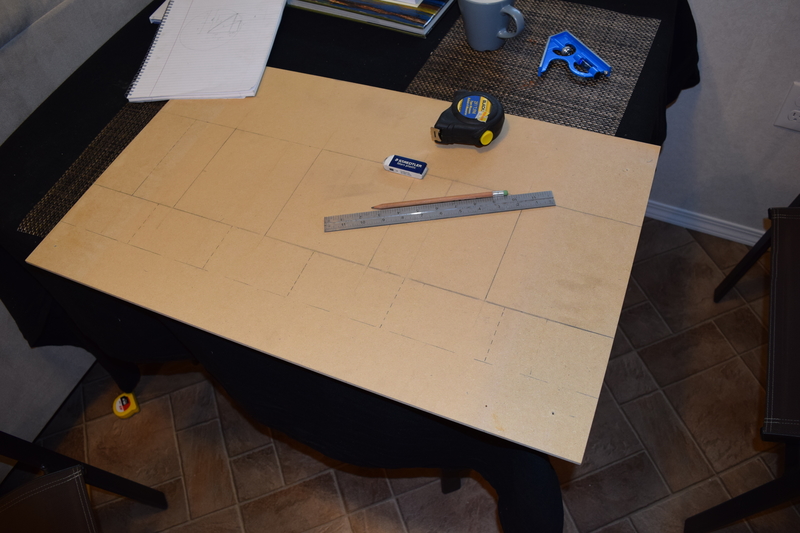

The most thrilling part of any project, I reckon, and the thing that drew me to woodworking is imagining and designing what you’ll create. You move the shapes and pieces around in your head, you visualise how all the things will interact, what people will do with it and how it will respond, how will it look, what kind of stress will it be subject too, what needs to fit in it and so on and so on. Eventually you line up all the parts in your head and draw out a plan.

Once the ideas have been drawn out on the wood (lots of erasing!) you start cutting.

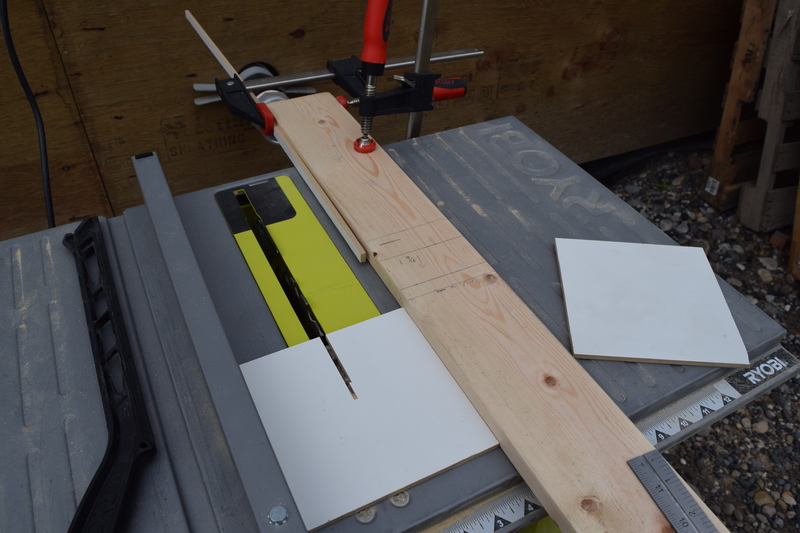

First up I tried cutting free hand on the table saw. Great way to mess up your materials. I experienced my first kickback. I put a little too much torque on the long piece I was cutting and the saw grabbed it and threw it back at me at ridiculous speeds. Luckily I was standing aside or I could have been injured!

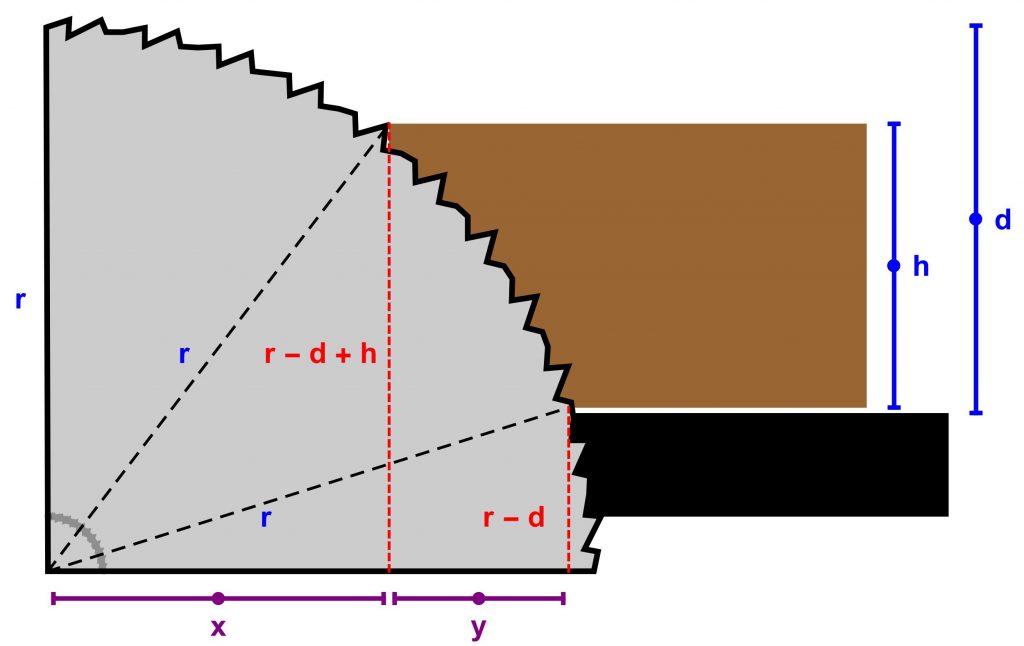

For someone with my terrible manual dexterity and abysmal artistic eye, measuring and clamping is a much better alternative. After figuring out the math (see previous post) I clamped guides onto my table saw and did the rest of my grooves precisely.

Unfortunately my grooves needed to be just slightly larger than the width of my saw blade. “Fuck it”, I said, “I’m not gonna waste time re-clamping all the damned guides, I’ll just free hand the extra tiny sliver on each piece.” Big mistake. Instead of spending 10 minutes clamping, I’d end up spending several hours with my chisel fixing my imprecise cutting job.

Still, a few hours after I’d started imagining, the thing I’d dreamed of was right there in front of me. It’s kind of satisfying to know that you can whip up a large range of things you need, especially up here where most things are impossible to buy.

It’s not perfect. There’s plenty of scuff marks on the white surface, a lot of the grooves don’t fit exactly right, and my plan to nail the back of the top shelf to the supports resulted in just splitting the damned particle board.

But! It holds up spices and that’s what matters in the end.