Recently I’ve been finding myself needing to cut a bunch of precise-depth grooves and I’ve only got a table saw to do it with. The trouble is, grooves are square and a table saw is circular.

One easy solution is to set the depth of the saw (i.e, how much it sticks out above the table, which you can do precisely) and place the piece of wood end-down over the blade. That way you’re sure that at it’s highest point—the middle—the table saw only cuts exactly as deep as you want it to. Unfortunately lots of pieces of wood are too long or ungainly to cut end-on.

Another solution is to feed the end of your piece into the saw in a rip cut, and to simply stop (or better still, clamp another piece to the table to act as a stopper) when you get to the required depth. Then you’d just need to turn the piece over and repeat on the other side, and then chisel out the little pyramid you’ve left in the middle.

The trouble with this solution is that while you can easily see how far the saw has cut into the top of your piece, but the bottom is hidden. How do you know at which point on the top of your piece to stop cutting in order to get a precise depth of cut on the bottom?

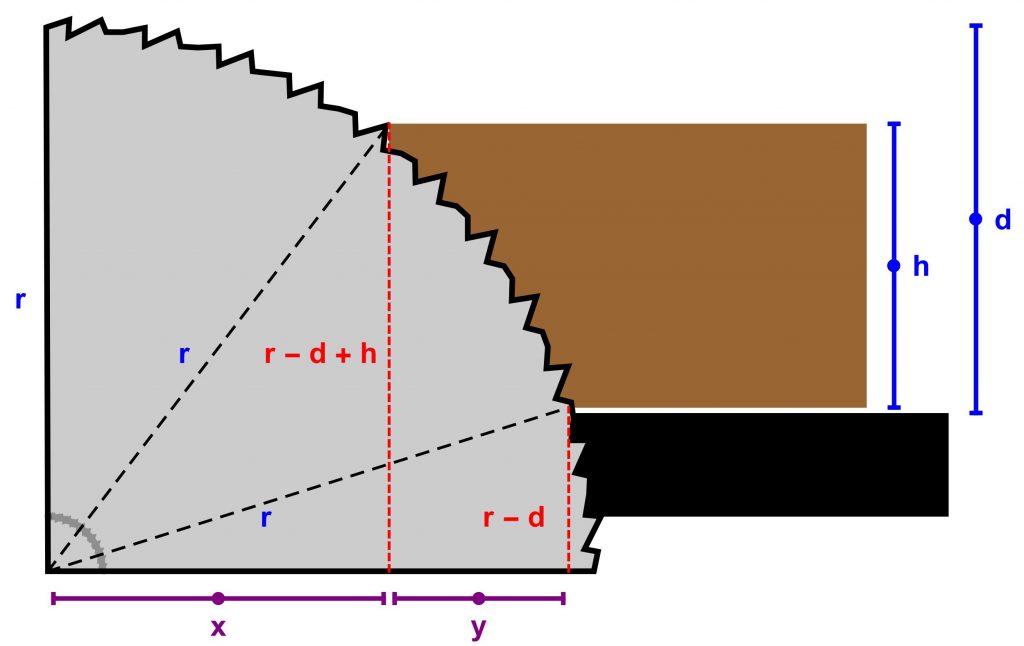

I cranked out the old high-school trigonometry (who said it would never be useful!) to figure it out. I also made a handy graphic to explain.

We know a few things:

- r: the radius of our blade

- h: the height of our piece of wood

- d: the depth at which we’ve set the blade (i.e., how far it sticks out above the table

This lets us figure out:

- r-d+h: how far above the center of the blade the bottom of our piece is

- r-d+h: how far above the center of the blade the top of our piece is

Knowing these lets us draw some triangle and then use good old Pythagoras to solve for the base lengths:

- \(r^2=x^2 + (r-d+h)^2\)

- \(r^2=(x+y)^2 + (r-d)^2\)

Solving for x and then using that to solve for y will let you figure out precisely how far in to the bottom of your piece the saw has cut, given where it is cutting the top. Here’s some simplified formula to save you borrowing your kids’ math books:

From [top cut point] to [bottom cut point]:

\(y = \sqrt{d (2 r-d)}-\sqrt{(d-h) (2 r-d+h)}\)

From [middle of saw] To [top cut point]:

\(x = \sqrt{(d-h) (2 r-d+h)}\)

From [middle of saw] to [bottom cut point]:

\(x-y = \sqrt{(d-h) (2 r-d+h)}\)

So, for instance, say you had a 10 inch blade (r=5) and wanted to cut a 3.5 inch piece of wood (h=3.5) and had extended 4 inches of the blade above the table (d=10). You’d have: x = 2.18, y = 2.72 and (x+y) = 4.9 inches. Say you wanted to cut exactly 6 inches into the piece, you’d know you needed to put a stopper exactly 1.1 inches beyond the horizontal center of the saw (just use a square to find and mark it) to get a perfect depth cut.