Before we left Vancouver, Faye and I bought a .22 caliber bolt action rifle.

While you can get a hunting license as a new resident in the North West Territories, there’s a tag fee of about $1,000 for each large mammal you shoot. On the other hand, if you wait one year, you magically become a better class of resident hunter, who only needs to pay about $20 per animal. Well worth the wait.

Our plan was to bring a cheap, small caliber (i.e., small bullet size) rifle up for year one. We’d do some target shooting and maybe get lucky and shoot a grouse or rabbit for dinner one day (small game licenses are cheap for everyone). Then, after a year, if we were enjoying going out shooting and wanted to do some large game hunting, we’d buy a larger caliber gun for year two.

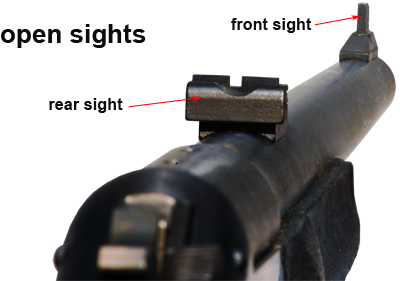

We also could have spent a whole ton of money (easily more than the rifle itself cost) to buy a fancy scope for it. Since we weren’t sure how much shooting we’d do, we decided not to buy the scope to begin with and just shoot with “open iron sights”. That is, by lining up the little metal widgets pasted to the top of the barrel.

Over the last couple of days, I wandered a fair way out of town to “zero in” the rifle, and find out whether we were going to regret not buying a scope.

Your vision along the barrel of the rifle follows a straight line, but the bullet coming out of the rifle is affected by gravity. To compensate, you shoot the bullet slightly upwards, so that it falls to exactly the height of your vision line at a preset distance.

The only adjustment we can (easily) make to our iron sights is raising and lowering the rear sight a tiny amount. My job was to set up the sights so the gun consistently hit the height I was aiming for at at a known distance. I also needed to figure out what distance that should be, based on how far away we are likely to be from small game (locals tell me you can almost walk right up to a grouse), and how badly my accuracy decayed with distance.

So I headed out along the winter road, tromping through the half-frozen ditches and bogs in my huge insulated gum boots. It’s cold out here these days, less than zero (Celsius, my dear American readers, where water freezes). But there hasn’t been any precipitation yet, so there’s not really much snow on the ground.

I found a steep hill, set up some cans a milk bottle and a pringles box, counted out the distance (25m) and started taking shots.

The first thing I learned is that .22 caliber bullets are so small and weak, they pass right through bottles, cans and boxes without even disturbing them. I was convinced I was missing because my targets didn’t even budge, but when I went to check them I found them full of holes.

All in all, I took 25 shots and hit about 9 of them. That’s 1/3 at 25m. Not ideal, but could be worse. The second thing that I learned is that random containers are terrible for sighting in your guy, since you have no idea which bullet hit where and how much you were off by. I wandered home, satisfied at having shot my gun, but no closer to having it zeroed in.

The next day Faye printed me out some paper targets and I went out again with a friend. I managed to sight in my gun at 25m and was consistently placing shots within about 5cm of where I was aiming vertically. However, I also found that the gun consistently shot about 5-10cm to the right of where I aimed, and there’s no easy way for me to adjust the sights horizontally.

All in all, better than I’d expected for a first outing with iron sights, but still not nearly good enough to take the head off of a small bird to preserve that delicious breast meat. Guess I’ll keep practicing.

So far the only animals I’ve see out there are ravens. Though, on the way home my neighbor and I stopped a while in silence to listen to the wolves howling in the distance.