The Mackenzie River is the largest and longest river in Canada. It discharges an average of 10,000 m³ of water a second. It is a powerful, powerful thing. People around here are rightly respectful of it, ourselves included. It is not uncommon for people to be swept away by it, to their deaths.

It is the second largest river in North America, after the Mississippi. Unlike the Mississippi, each year that massive movement of water turns into a single solid mass of ice.

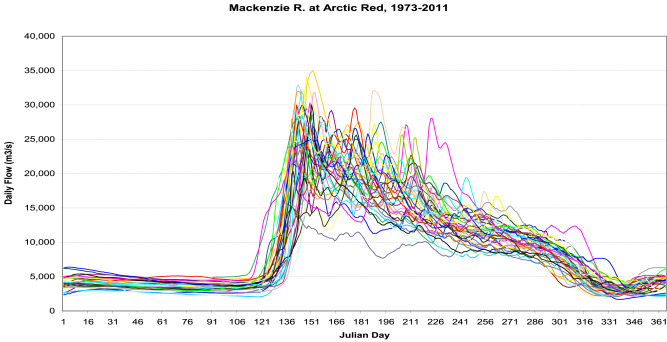

When the Mackenzie breaks up in spring, it’s not like other frozen rivers. It doesn’t melt gently. The ice does not gradually get thinner until it opens up to water. The Mackenzie breaks it’s icy crust, it does so by smashing against it with 30,000 cubic meters of water a second.

The Mackenzie runs south—where it’s warmer where ice melts sooner and tributaries run stronger earlier in the year–to north—where it’s mouth at the the arctic ocean is still a single massive block of ice.

The power of all the melting water builds at builds, pushing against the still-frozen sections of river progressively further north.

At first you hear a tinkling sound, like glass panes breaking far away.

Then the still-meters-thick sheets that have been your road for months begin to crack.

We missed the main action because it happened at night, but came out in the morning to see the river had turned into a vast field of randomly jutting icebergs.

The process moves north (it would be amazing to watch from a plane or satellite) until all the newly ruptured ice gets trapped at the rivers’ bottlenecks. And then the pressure begins to build to the south and the waters begin to rise.

The endless sea of ice chunks moves too slowly for anyone but the most patient observer to witness, and yet over the course of days the river rises tens of meters. The shuffling ice giants rip trees and other detritus from the banks; others are dredged from the bottom by the slow but unstoppable churn.

And then the ice at the bottlenecks melts enough for the pressure to break through. What was a sea of jutting icebergs suddenly develops a flowing fast-lane of water through its middle. The water level quickly drops and all that’s left is an impassible wall of broken boughs and still-melting ice chunks, high up above the usual waterline.

Heaving machinery from the quarry comes down to clear the debris from the road. Not long after the locals begin collecting ice from the remaining chunks for making tea with.

The town sent us these warnings:

“Attention. The Hamlet of Tulita is monitoring the River. If the Ice and Water begin to rise and impose upon our residents of Big River drive the fire siren will be turned on. This will be the signal to evacuate houses on the flood plain. There will be Hamlet and Tulita Fire Rescue staff and RCMP on scene to help.”

“People please. THE ICE IS STARTING TO MOVE. DO NOT BE CLIMBING AROUND ON IT. WE DON’T WANT TO HAVE TO CALL OUT S&R.”