WARNING: This post contains potentially disturbing images and words.

Most of the time, it feels like we—you and I, reader—are magical, immortal essences, floating somewhere behind our eyes, safe in our solid, complete, inviolable bodies. Alright, sure, it doesn’t feel exactly, acutely like that. Most of the time it feels like we’re a bit hungry and have an itch on our shoulder. But when we think about ourselves, our sense of what we are, it most certainly doesn’t feel like we’re squishy, fragile, clumps of brain matter in a fragile meat bag. It’s easy to understand why notions of an “immortal soul” are so common across cultures. Even when all evidence we see says that we’re actually just clever sacks of flesh, guts and gooey brain matter, just like all the other animals, its hard to shake that gut feeling that there’s something permanent, almost magical, something that essentially *us* lurking behind our eyes.

I think the sense that we’re more than just meat is partly why people find it upsetting to think about their own death and mortality. We might know, rationally, that we’re one sharp poke away from spilling our insides all over the floor and becoming inanimate, lifeless goop, but its only rare moments in your life that you ever really feel the truth of that deep in your gut. For me, one of those moments happened recently when, after an hour and a half of inexpertly sawing apart its skull with a crappy hacksaw, I was digging around the base of a wolf’s skull trying to fish out its brain.

But maybe I should start from the start.

I got an email from my old PhD adviser. A colleague of his at the university was setting up a lab that would try to understand dog evolution by comparing wolf and dog brains under MRI. She needed wolf brains and he knew I lived up north where people still hunt wolves. We got in touch and I gave her some tips on how to contact hunters or taxidermists or government biologist in regions where they were conducting wolf culls. I also, on a whim, offered to do the leg work for her and get it all set up, if she wanted to pay me a bunch of money instead of doing it herself. She did.

I contacted ENR (Environment and Natural Resources; a branch of the Northwest Territories government that oversees anything to do with animal harvest), told them my situation, and asked whether they could help me get a wolf brain for research purposes. At first, the local ENR staff were keen and helpful. They shoot problem wolves all the time, and their local biologist could chop out one of their brains no problem.

I filled out the paperwork for a scientific research permit and was ready to go. By this stage, my request had trickled up the bureaucracy. Administrators in Yellowknife became involved and it quickly started to seem less and less likely that ENR would do anything, let alone do anything quickly. ENR’s chief veterinarian insisted that it was impossible to extract a wolf brain with a special, expensive, custom-made vice that she had commissioned for herself.

Around the same time, one of my neighbors was hunting for a wolf. His plan was to use its pelt to make winter garments for his family. I’d talked to him about this whole weird wolf brain contract that was on my plate, and he said he’d let me know if he shot one. Fast forward to March 27th. The sun was setting and I’d just spent about 5 hours unsuccessfully trying to repair my snowmobile. I was covered in grease and feeling a little disappointed when the phone rang. My buddy had shot a wolf about 4 miles out of town. He was on foot and needed help bringing it home.

Now, reader, there’s a few extra circumstances you’ll need to understand to grasp the ridiculous drama of the few hours that followed.

Let’s do it as a list:

- The researcher needed the brain to be removed from the skull and place in formaldehyde as soon as possible after death.

- They also needed it to never be frozen.

- There was still snow on the ground and at that time of year, temperatures feel below freezing fast after sunset.

- I have a small quad (see: 1, 2, 3), a 4-wheel ATV, that could probably precariously fit myself, my mate and his wolf carcass, but one of its tyres had a slow leak which had been getting faster. With a good pump up, I estimated it could go maybe half an hour before it was flat.

- Daytime temperatures were above freezing, so the winter road was fast becoming mush. Within a few weeks it would be impassable bog, and there were already plenty of precarious sections where I’d need to blast through, praying that the ice was thick enough, the mud shallow enough and my quad light enough to make it.

- Wolves, especially northern wolves, are big. They’re not like you’re family pet dog. They can easily weight 100-150lbs (45-70kgs), and my mate had shot a big one.

- There’s one store in town, and it sure as hell didn’t stock formaldehyde. In a stroke of amazing luck, another friend in town had some left over formaldehyde that they could give me, but only enough that I would get one shot at this. If I messed this up, it was going to be next to impossible to try again.

I raced home! I frantically pumped up my leaky tyre. “Hold you damn tyre! Hold!” I literally screamed out loud at it. I blazed across the half-frozen bog on my machine, flying through muddy ice and icey mud, wind in my face, everything turning slowly orange from the sunset behind me.

I found my mate out in the bush, exhausted from hauling the heavy beast on his shoulders even a short distance. We strapped it to the quad, it’s head dangling off one side, it’s back legs and tail off the other, my mate precariously perched beside it. We were off!

It was about a half hour’s ride back through the frozen bog, last rays of sunset vanishing ahead of us, the chill setting in. Dancing my machine through each section of ice and snow and mud, fast enough to not get bogged, fast enough to get back before the tyre completely flattened, slow enough to not lose control and kill my buddy.

Here’s the moment I’ll always remember. “Go slow! Go slow!” my mate was shouting behind me. The wolf behind him, its head bouncing with the off-road terrain, long tongue lolling out, looking disturbingly like a dog. Bear Rock ahead of us, catching the very last colors of setting sun. And me, standing at the helm, leaning hard left with all my strength to de-weight and counteract the fast flattening tyre, desperately trying to get us back before the wolf froze and us along with it.

We got the wolf to my mate’s place, cut off the head and I took it home. Then the real work began.

Since the ENR vet had said she needed a fancy vice to extract the brain, my plan was to stick the whole head in formaldehyde. But the other biologists sitting around my house that evening told me that it wouldn’t work. The formaldehyde wouldn’t penetrate deep enough to preserve the brain unless it was extracted.

I don’t have any specialist medical tools, but I did have my woodworking tools, which included a hacksaw. So, I started chopping. At first I tried to cut off the snout, thinking I could just cleave off bits until I isolated the brain case and could carefully get inside it. That didn’t work. A wolf’s snout is full of sinuses, cavities and teeth. All bits that catch your shitty hacksaw and are ridiculously hard to cut through.

Then Faye had a brilliant idea. We have a vet friend in Vancouver. We gave him a call. Without a moment’s hesitation, he took the whole situation in his stride and told us exactly where to cut. Four waypoints on the wolf’s skull—between the eye ridges, the lump on the back of the skull, the indents near the ears on each side—that if I cut between them should give me clear access to the skull.

I got cutting. By this time it was late at night and Faye, her biologist friends and even my vet in Vancouver had gone to bed. I kept on cutting, sawing through the skull of something that had just a little while earlier been alive, something that when I looked at it sometimes, disturbingly reminded me of the dogs I’d loved as a child, my companions.

At first, over cautious, I cut the hole too small. The eyes were a problem too. It was hard to cut at the right angle without poking them from behind with the front of the saw, making them squish and compress in a deeply unsettling way. Eventually, to make room, I had to cut away the eyebrow ridges, reach in with my fingers and pull the eyes out. It was about this point that the deep awareness of my own frail mortality was really setting in.

Gradually the hole in the skull got bigger and bigger. Finally, after what felt like a whole life spent cutting wolf bone, the hole was large enough to reach in with my fingers and scoop out the brain. I had thought it would be deeply connected to the skull and rest of the body, but besides a few tiny filaments attaching it to the skull base—like the finest of threads, that snapped easily with a fingertip’s worth of pressure—it just slipped right out into my hand.

And now we’re back to where we started. I stood a while, holding in my palm the entire physical medium of what had a few hours earlier been a thinking, feeling, distinct individual. Realising, understanding, viscerally, that this was all I was too. Just white, soft, pliable brain matter, so loosely attached, that someone could, with a few tips from their vet, cut out and hold in their hand.

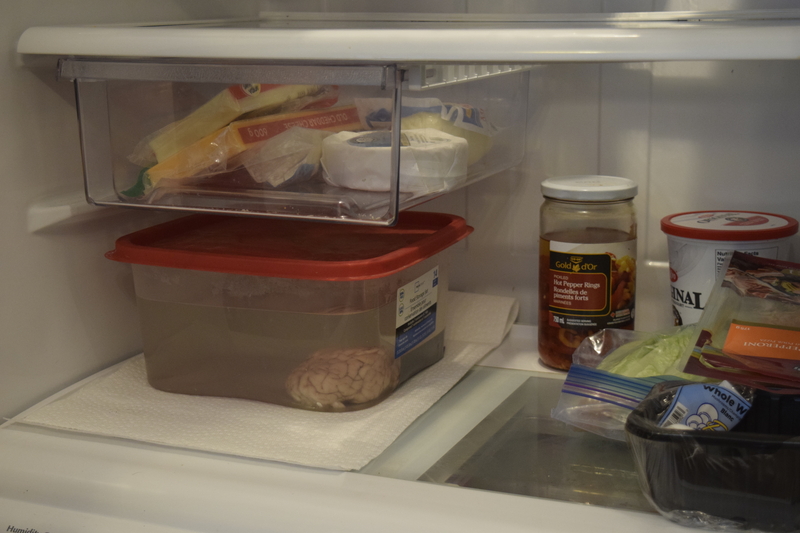

Formaldehyde is pretty carcinogenic so, I suited up in rubber kitchen gloves, cheap plastic glasses and a balaclava to pour it and the brain into a plastic kitchen container. I vacuum sealed the whole thing up and stored it in our kitchen fridge for the next month or so, while I figured out the obnoxious piles of paperwork required to legally ship it to a university in America.

In the end, it arrived safely. The researcher named it: Wolfbrain Amadeus Mozart.

There’s one more harrowing part to this story. Two days later I was out on the winter road. Checking my rabbit snares and just generally getting outdoors. I heard wolves howling. There’s a wolf pack whose territory includes the area near town, so that’s not unusual. I heard plenty of wolf howls before, but goddamn this was different. I swear to god it sounded like they were howling in sorrow. It went on for ages and ages, and with layers of what sounded like mournful agony piling on top of each other. Maybe I’m anthropomorphising. Maybe it was just normal wolf howling and my own emotions changed how I interpreted it, but it affected me regardless.

I don’t think I’m going to be involved in any more wolf harvest. They’re too much like people. I don’t feel morally culpable in any way for this wolf’s death. It wasn’t my demand for a wolf brain that got him killed, he’d have been hunted for his fur anyway. The head would have been thrown away if I wasn’t there to salvage it for research. But still… I don’t think I want to be involved.